Almost five years ago, my then-domestic partner/now-husband, our two pets, and I, packed our things and moved away from San Francisco’s Potrero Hill neighborhood. The little condo had been my home for over five years, and as is often the case with homes freighted with emotional memory, I wandered the empty space we were about to leave forever, and teared up a bit.

I was lamenting for more than just reasons of nostalgia, though.

My tears were because we were leaving Bougiestan.

That’s my name for it, portmanteau of bourgeois and -stan, the Persian suffix for land or place (hence Pakistan, Turkmenistan, etc).

Every city’s got these places, well-manicured, upscale neighborhoods of charming older homes, or sparkling new McMansions. I’m not talking just about areas of huge affluence, the Billionaire’s Rows sprouting in a few global cities. No, Bougiestan’s bigger than that: it includes places like Shaker Heights, Ohio; Overland Park, Kansas; The Woodlands, outside of Houston; Philadelphia’s Main Line suburbs; Chicago’s North Side and North Shore suburbs; Palo Alto, California. Pretty much every economically-significant metro area’s got a Bougiestan, the primary nesting grounds of the upper-middle class.

How My Family Got There

Nobody alive today knows exactly how my forebears gained admittance to this realm. Sometime in the early 20th Century, one of my grandfather’s brothers moved to South Africa from Eastern Europe, and hit it big there. His wealth spread to other members of that extended family as they leveraged those connections to establish themselves all over the globe. After the Second World War, my grandparents moved to Canada. Although they lost most of their prior wealth in the decade that followed, they nonetheless held on to just enough to remain in Bougiestan. My father, availing himself of the rising postwar economy, kept the party going as a corporate attorney right through my childhood. Only in the stagflation 1970s did my family’s socio-economic situation come under threat, an anxiety that hung over our household for all my teens and beyond.

For me, however, the die had been cast: the notion of not living in Bougiestan seemed unthinkable. Even in my early years as a wannabe screenwriter and office temp, I always lived in or near upscale neighborhoods—even if only in a studio apartment. While I was fiscally careful about it, for others in my sphere it often meant repeating my parents’ mistakes, overextending themselves to live the lifestyle of their well-to-do cohorts. As offspring came into the picture, the urgency of Bougiestan becomes doubly significant: after all, good neighborhoods have good schools and good amenities…so not living in those places must be tantamount to child neglect and abuse.

Trouble in Paradise

But is it? My own memories of bullying and social ostracism—driven partly by the fact that my parents struggled to get by in our little Bougiestan—suggests that life in there isn’t always better. When Tom Hanks’ character in the 1993 film Philadelphia, brings his Latino boyfriend, played by Antonio Banderas, to the Bougiestan he grew up in, Banderas scoffs. He can’t imagine the place being anything less than idyllic. Hanks replies: “those can be some pretty mean streets. Don’t let appearances fool you.”

While there’s obviously nothing wrong per se with aspiring to live in such places, Bougiestan carries with it much of our current conversation about inequality and the vanishing middle class. It’s also a physical manifestation, in America at least, of the country’s tortured racist past, something I myself wasn’t cognizant of when I first came here two decades ago.

A History of Nice Neighborhoods

Even the most illiberal of people now agree Southern-style segregation was wrong. Jim Crow is practically shorthand for racial injustice, to say nothing of South African Apartheid or Nazi-era Nuremberg Laws.

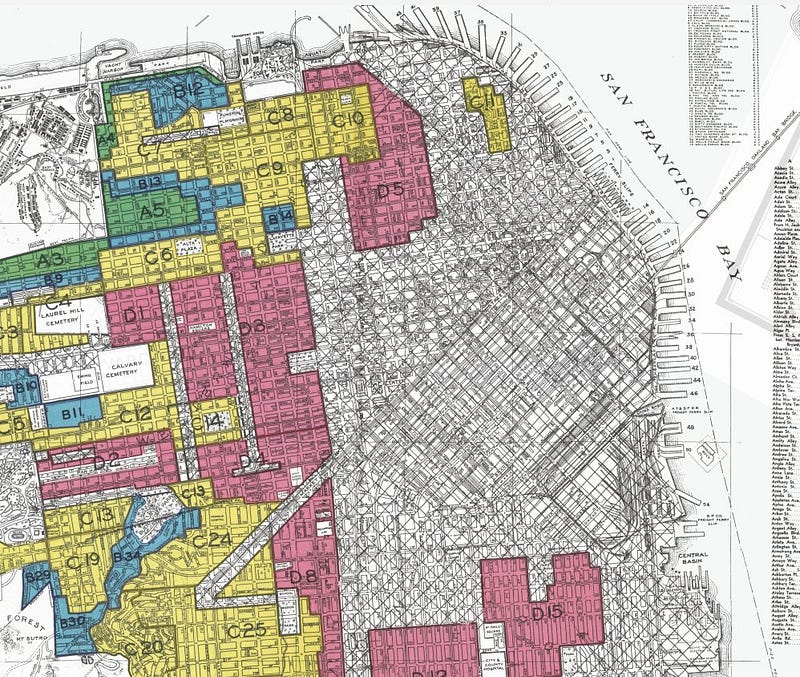

But the reality in America is more nuanced than that: from the 1930s right through the 1960s, banks in America engaged in the practice of redlining, of literally drawing red lines around economically disadvantaged, mostly minority districts, and refusing to lend there. Conversely, many interwar suburbs, Bougiestans both back then and continuing to today, enacted racial covenants prohibiting people of color from residing there.

While this obviously doesn’t mean that every resident of Bougiestan today is racist, it does mean their lives and lifestyles are built upon that legacy. It means that the property appreciation those people enjoyed, and continue to enjoy, was not shared by all. If there’s one thing our move to a onetime non-Bougiestan neighborhood—rapidly becoming part of Bougiestan thanks to San Francisco’s real-estate market—taught me, it’s that turning a place into a Bougiestan costs money. Big money. All those lovely landscaped yards and gut-rehabbed interiors involve huge expenditures of skilled labor and cash—something that’s in short supply to nearly all of the population.

My own crocodile tears upon leaving Bougiestan, though, pale compared to how many others see it. It’s perhaps best expressed by a character in an episode of the HBO TV series Big Little Lies, itself set in a Northern California Bougiestan community near Monterey. Laura Dern’s character, wife of a financier, learns her husband’s been convicted of Bernie Madoff-like financial crimes. Her family’s economic standing in jeopardy, she freaks out, and shouts at him:

“I will not not be rich!”

If Not Bougiestan, Then Where?

Dramatics aside, Bougiestan is really just a manifestation of our era of rising inequality, of hyperinflation in critical domains such as education, health care, housing, and retirement. Bougiestan’s residents, in a way, only exacerbate the problem, hoarding the opportunities available to them. In many ways, this isn’t their fault, at least not entirely: while the upper-middle class have undoubtedly benefited from the last four decades of “greed is good” capitalism, its biggest winners and instigators are the truly rich, the rentiers, the financially independent whose income is passive and not primarily earned through wages.

While there are many standouts among this class who’ve rejected the status quo and look to fix it—Bill Gates, Warren Buffett, and Marc Benioff stand out—too many follow the path of Roger Ailes, Richard Mellon Scaife, and the Koch brothers, for whom inequality is not a problem to be remedied but an inescapable, unchanging reality of the human condition. There will always be poor people, said one young conservative to me at a job at a Midwestern bank years back, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

I reject this notion, and believe that more than just social policy can fix it (though I support that as well). For all our technological innovations over the past few decades, we in fact live in an era of declining productivity and growth. Most innovation these days is focused on small-ball communications technology (do we really need another social sharing app?) or finance of the type that nearly wrecked the world economy a decade ago.

Fixing the Real Problems

This has been good in Bougiestan, for those talented, lucky, and assertive enough to remain in it, but it’s likewise left many millions behind. Compare these last fifty years with the century before it—between 1870 and 1970—when the world catapulted itself from a largely impoverished rural or early-industrial existence to a cornucopia of airplanes, moon rockets, labor-saving, affordable appliances, mass transit and automobiles—and even the foundation of our more incremental-improving times, the microprocessor.

Technology isn’t the absolute savior, but as rapper Macklemore put it about another social cause, it’s a damn good place to start. Bougiestan and the housing crisis are in fact the same issue, for as long as housing is rare and expensive, even the most basic, Levittown-style living will be unattainable to most.

But what if we could leverage technology and automation to build housing at one-tenth the cost it is now? Construction is an industry that’s hardly changed at all in centuries. Look around at your home: every cut piece of timber, every brick laid, every drywall panel in every building ever built was applied by hand, with human toil and sweat—just as was done in the time of the Romans. Sure, we have power tools instead of slaves, but little else has evolved. There have been moves in prefabrication here and there, but nothing that’s moved the needle in any big way.

To that end, the biggest thing that’ll make Bougiestan, or at least more of its trappings, available to everyone, will be the will to make it happen. As World Wars, moonshots, and disease-eradication projects of the past have proved, humankind possesses immense potential to reshape the world. But it’ll take earnest commitment, concerted initiatives—and maybe a little sacrifice—from everyone, in Bougiestan and beyond, to make it happen.

Leave a Reply