For those of you following my stories through the years, you have an idea where I come from.

I’m WEIRD.

By that I don’t just mean strange or peculiar (though I’ve been called that as well); I mean the phenomenon that’s been noticed among psychologists looking at who participates in their studies. An overwhelming number of them hail from the same background: Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic (WEIRD) societies.

Basically, the most fertile breeding grounds for—and the biggest practitioners of—that thing known as meritocracy.

Meritocracy: a good thing, right?

The concept of rewarding people based on merit isn’t exactly new; it’s basically seen as a synonym for the modern era, at least in the West. Spurred on by the Enlightenment, and the idea that human life and human beings are improvable, leaders such as Napoleon put forward the notion of careers open to talent early in the 19th century. Nowadays, we take it so for granted that the idea of going back to a world of inherited privilege seems unfair and absurd.

Plus, we need look no further than the enormous advances of the last two centuries as proof that meritocracy works, as the world moved from subsistence-level agriculture to jet planes and the internet. Obviously that’s because we adopted this new and better way of rewarding people, right?

Turns out the answer’s not that simple.

I’ve been following for some time the writing of one of meritocracy’s own whose become one of its harshest critics, Yale professor Daniel Markovits. I finally took the plunge and read his book on the subject—and it’s a sobering, all-too-accurate portrait of our crazy, fraught, competitive world.

Markovits reminds us that the originator of the term, in the book that first described meritocracy’s rise, actually meant it satirically and critically. Only in later years did meritocracy’s proponents claim the term as a good thing.

But how can something that seems on the surface to promote fairness and encourage people to excel…be bad? I’d break out Markovits’s argument into two parts: the unfairness meritocracy ultimately creates, and the not-really-better world of jobs meritocracy builds.

Meritocracy creates a new kind of unfairness

This one’s a both obvious and controversial claim for anyone who’s been alive over the past half-century. Basically, Markovits claims that meritocracy, and the rise in inequality in America over the past five decades, are one and the same phenomenon.

On the surface, the probably seems ridiculous. If meritocracy is supposed to distribute opportunity more fairly than a society of oligarchs or aristocrats, then how can it possibly lead to more unfairness?

The answer is proved by history. As meritocrats rose in status, they helped tilt the game more and more in favor of themselves. Sure, the daughter of a CEO is expected to work hard in school and in the jobs she lands afterward. But even with parents who try not to inundate her with advantages, the privilege is there: chances are, even if she goes to public school, it’ll be a better-run, better-funded public school than those of her poorer counterparts; even if her parents don’t openly cheat to get her into college, she’ll still benefit from better coaching, tutoring, and other preparatory steps to get her into the highest-status schools. Her better jobs will ensure better-quality, subsidized health care for her and her own descendants. Throughout her life, she’ll exist in a bubble with other people of superordinate status, and will imbibe and benefit from their elite standing and practices.

Sounds a lot like aristocracy, right?

For those who vehemently disagree, and claim that harder and more productive work should be better rewarded, I present Markovits’s second point.

Meritocracy warps the very concept of “work” itself

Proponents of meritocracy, and even of meritocracy’s excesses, always make this point: in meritocracies, people are rewarded for the value they create. We dare not go back to a Soviet Communist world, where doctors were paid the same as janitors, and nobody had the urge to work hard or innovate. Go that route, and we’ll end up collapsing the way the Soviet Union did in 1991.

A further case for this was made when the mid-century American corporate world structure was dismantled in the “greed is good” 1980s. In fact, that speech, given by character Gordon Gekko in the movie Wall Street is on that very subject: in it, he describes the sclerotic layers of middle management one of the companies he’s trying to wreck consists of. Dozens of vice presidents shuffling memos to each other. Overpaid, mid-skilled employees leaching profitability from shareholders. Just get rid of all that bureaucracy, and let true meritocrats reign.

It’s an alluring, seductive notion, and it’s captivated us for decades: if we can replace 33 vice presidents each earning $200,000 a year (the figures Gekko cites in the film) with one high-achieving CEO who earns $2 million a year in salary—plus many tens of millions in stock appreciation earned by slashing company payrolls—well, on balance, that may seem like a good deal. At least, for the meritocrats, it does: a small number of their superordinates drives the company to profitability.

But never mind the dozens of mid-level execs—and the thousands of mid-level workers—who are thrown out of work. For many of them, the only option will be to find new work in what Markovits calls “gloomy” jobs: low-skill, low-paid work in retail and services.

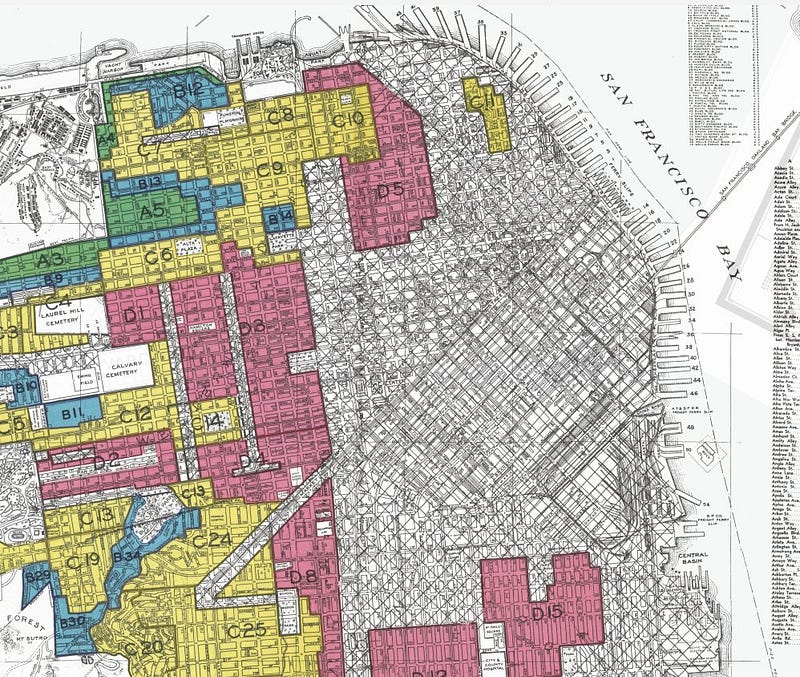

Meritocracy’s tale of two suburbs

To further exemplify his case, Markovits compares two American suburbs, Saint Clair Shores, Michigan, and Palo Alto, California. In the mid-twentieth century both were respectable middle-class towns, housing workers in automotive and electronics industries. Fast forward half a century to find one of these places—you can guess which—drastically weakened by the destruction of its middle class base, while another is super-concentrated by elite meritocrats in “glossy” jobs, who snap up its once-midrange homes for millions of dollars.

But there’s more to the destruction of the middle class than jobs simply bifurcating into “gloomy” and “glossy.” What happens is the actual jobs themselves change in character. Mid-skilled bank loan officers become low-wage data-entry clerks; meanwhile, investment bankers, who securitize and sell the mortgage-backed securities that are what home loans ultimately become, require ever-greater skill, training, expertise—and compensation—to do what they do. Every year, the derby to get into elite colleges to land this elite training to land these elite jobs gets keener and keener; every year, fewer and fewer people make more and more money, while an ever-greater share of the population languishes in economic obscurity.

The results of this are obvious on the bottom rungs of society: for the first time in generations, life expectancy is going down in America (even pre-Covid). Addiction to opioids rises as whole swaths of society find themselves increasingly irrelevant. Meanwhile, on the upper tier, things aren’t much better: as competition heats up to land in or stay in the elite, superordinate workers endure insane work hours, and growing pressure to be ever more productive, to add ever more value to the enterprise in order to retain their earnings, standing, and status.

What is to be done?

Markovits ends with only rough outlines of solutions, and I can see why: nobody’s really figured out a path forward out of this mess. His suggestion that jobs themselves get redistributed is a toughie, likely involving German-style vocational schooling, and possibly even moves toward universal basic income.

Why aren’t moves like these already being made, or at least tried? Well, the history of inequality itself, paints a gloomy portrait: the only way societies have ever really pushed reset on inequality is through massive upheaval. To wit: world wars and bloody revolutions. It’s a bleak picture of humanity, yet one many meritocrats cling to. “Nobody cedes their privilege,” says one of the characters in The White Lotus, a recent HBO series about the well-to-do vacationing at an elite Hawaii resort. For the sake of humanity’s future, I hope we figure out a sane way to do so.

One way to think more constructively is to recast some of what drives meritocracy. Where wealth of a different age prided itself on its idleness, today’s meritocrats cite their hard work as a defining virtue. I think a lot of this comes from the so-called Protestant work ethic, which holds labor and industry itself as virtues.

Now, I do agree there’s some merit to that. If nobody did any work, we’d have long since died out as a species. And even fictional, egalitarian, post-scarcity societies such as those in Star Trek (a favorite go-to of mine) see folks laboring mightily to build starships, explore the galaxy, and excel in their achievements. I don’t think the spirit of accomplishment itself needs to die out. I don’t even think the notion of healthy reward for initiative and creativity is entirely misplaced.

What is misplaced is the notion that we need to be always on, always all cylinders firing, all the time. “Only the paranoid survive” was the title of a book by one of Intel’s founders. But must we be so paranoid to invent iPhones? Once there was a notion that we as a species actually, on aggregate, would work a lot less, once we figured out how to meet all our basic needs—food, housing, economic security—through the technical advances we were making. With these taken care of, we’d be even freer to innovate, to use our merit to build things we wanted, and continue our processes of societal improvement.

Even in such a world, there will always be those who labor mightier, whose talents are indeed greater, and will no doubt enjoy rewards and prestige for doing so. But I think they, and everyone else, would do even better work in a world where there wasn’t a proverbial gun to our head to do so—a gun that in this age is largely one of our own making.