“I had always felt that the Devon School came into existence the day I entered… was vibrantly real while I was a student there, and then blinked out like a candle the day I left.”

– John Knowles, A Separate Peace (1959 novel)

How many of us think that not just about school, but about the world itself? Probably every human that has ever lived imagines the year of their birth is the most important in all the years that ever were.

That said, some lay better claim than others. Call it my corollary to the quote ascribed to Lenin about weeks when decades happen. I’m betting Germans born around 1989 think so about their year, as do Americans birthed in 2001. Or, for that matter, most anyone born most anywhere in 1945.

To that end, I’d like to submit 1970 into the roster.

Qualification One: I’m talking more about the small cluster of years around it, the late-nineteen-sixties and early seventies. Qualification Two: I’m largely focusing on the United States and Canada, though there’s sizable relevance to other Western countries, and, by extension, the rest of the world.

The overall bigness of 1970

Not just that it’s a round number — always convenient for counting birthdays. Though a part of me wonders if, given our base-ten numbering system and our generations lasting about twenty years, we tend to subconsciously bring about cadences, ebbs and flows in time that match our notions of major markers. Whatever the reason, it’s been widely noted that after 1970, things just… shifted.

The decade before it offers clues. Love ‘em or hate ‘em, few deny the impact of the Sixties. The decade when the Betty Crocker post-World War II family order began breaking down. The promise of that order worked out great for straight, white, cis guys… but for practically nobody else. Agitators for change made it out there in the 1960s, but it wasn’t until the coming decade that change became reality.

That’s evident in two big trends: the ending of the draft in 1973 and the shift in women admitted to college since then (interestingly, the charts for this trend all seem to start in 1970).

Queer(er) Nation

1967 may have been the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, but 1970 was the era of Stonewall. Not initially considered a big deal by mainstream society—and by no means the only LGBTQ+ uprising to have happened back then, it nonetheless stands out. A for-real uprising against the police — a police, of the time, enforcing purposeless, horrifically persecutory laws. Laws that criminalized certain groups right to meet one another, to find connection, experience love. One year after the riots, the earliest marches of what we now know as the Pride movement started. Both happened within months of my arrival on this world. You could say I was literally born with Gay Liberation (though it took me awhile to figure it out).

Actually, that’s another disclaimer: big change sometimes takes time, and only looking back do we trace its spark. Even though I’d grown up mostly after being LGBTQ+ had been removed from psychiatry’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual as a mental affliction, I personally can speak to that notion having persisted for way too long in society. Don’t believe me? Watch any John Hughes 1980s high school movie. The Stonewall spark built very slowly to the roaring blaze it is now.

But it got lit around 1970.

Sex, drugs and rock ‘n roll

“They are not your friends… and they will ruin rock and roll and strangle everything we love about it.”

– Cameron Crowe, Almost Famous (2000 film)

Music’s probably the first thing people think about when they talk about the 1970 barrier. The violence at the Rolling Stones concert at Altamont Speedway in December 1969 is where many analyses start. It led to greater professionalization of the industry, those big arena rock shows of the seventies.

Then, in 1970, the Beatles broke up. Come to think of it, the arc of their career traces the big social changes that brought us to 1970. A decade before, guys took ladies on a date to a supper club for some ballroom dancing, as they had for generations. Ten year later, it was nightclubs, LSD, and the hippie-hippie shake amid a newly-free college generation. Don’t believe me? Watch Mad Men through its entire run. Or read about the demise of in loco parentis.

From noble causes to Pentagon Papers and Watergate

“You had Kennedy. I didn’t. I’ve never heard a president say ‘destiny’ and ‘sacrifice’ without thinking, ‘bullshit.’ Okay, maybe it was bullshit with Kennedy, too. But people believed it.”

– Mike Nichols, Primary Colors (1998 film)

The Sixties bore the curse of interesting times. For all the idealism, things were far from idyllic; heck, the world nearly ended before the decade was even halfway out. But a certain broader idealism feels like it was lost. When Ron Kovic goes off to war in Born of the Fourth of July (not my favorite movie, but bear with me here) sometime in the Sixties, his town is all golden and gauzy; when he returns, the Seventies have dawned, and the place is dirty and run-down.

It’s a malaise that had tangible turning points: in June, 1971 the Pentagon Papers came out, detailing what America’s government was really up to in Vietnam. Looking back, it seems almost unfathomable—in our age of smartphones, nonstop news, and five decades of jadedness about military misconduct—to really picture how long stuff like this took to disseminate, and how earth-shattering it was when it did.

But when it finally all came out, it shifted the paradigm: a government and military that, a mere quarter-century before, had led the Greatest Generation to heroic victory in the Second World War was now up to no good, destabilizing the very world people thought they were saving. Even the military-industrial complex’s most sacred offshoot, the space program, saw its mighty, decade-long initiative come to fruition in the summer of sixty-nine. Think of space exploration what you will, we’re still struggling to exceed what was all over and done with by the time the New Years bell rang on 1970.

With Apollo-era heroics closing, a darker door was opening. A gate, actually. Or, rather, a building named for one: Watergate. So central has it been to the notion of government scandal, crime, and cover-up, that the suffix -gate is now applied to nearly every scandal since.

The tipping point of economic inequality

From Robert Reich to Thomas Piketty, economists and thinkers are nearly unanimous in declaring 1970 the rough threshold where economic inequality in Western countries — America most especially — began to rise.

My take on why is actually related to the above: after they failed to snag a lock on Betty Crocker conservatism in the Sixties, the crowd so inclined to such ideas went in another direction. They even had a perfect pretext, thanks to another series of events that happened around 1970. Back then, and still now, humankind’s most vital ingredient to make the modern world happen. A three-letter word: oil.

Specifically, the OPEC embargo of 1973. To an even greater degree than the whipsawing economy of the past few years, the 1970s oil shocks roiled America. It all happened care of another peak: America transitioning from a net oil exporter to oil importer (something that’s only been partly reversed in our time of fracking).

These were the real causes of 1970s stagflation, an economic reality that was the very opposite of the go-go decade before. Adding to it were America’s once-defeated, now-rebuilding economic rivals starting to mount a challenge to U.S. manufacturing. With everything feeling like it was going downhill, it’s no surprise that challengers to the liberal economic consensus came out of the woodwork.

We all know what happened next: the Reagan era, Morning in America, the complexities and contradictions of the 1980s. They accelerated and reinforced a self-fulfilling prophecy, one where it’s believed the only way toward “progress” is through a greater risk/reward mechanism, one that leads, seemingly inevitably, toward ever more unequal outcomes. Whether or not you agree that this is inevitable (I sure don’t) the fact is, the movements that pinioned around 1970 were the forces that shaped our times.

The New Hollywood

We already went through music. But there’s another cultural touchstone that got a major rethink around 1970. Old Hollywood had been on the decline for years — by which I mean the system of studio bosses, vertical integration of production and distribution, capped off with Production Code-mandated soft censorship that forced movies to be redemptive and wholesome. By 1970, the Production Code was repealed, and as film critic Michael Medved once remarked, the winning Oscar for Best Picture went from movies like The Sound of Music, in 1965, to Midnight Cowboy in—you guessed it—1970.

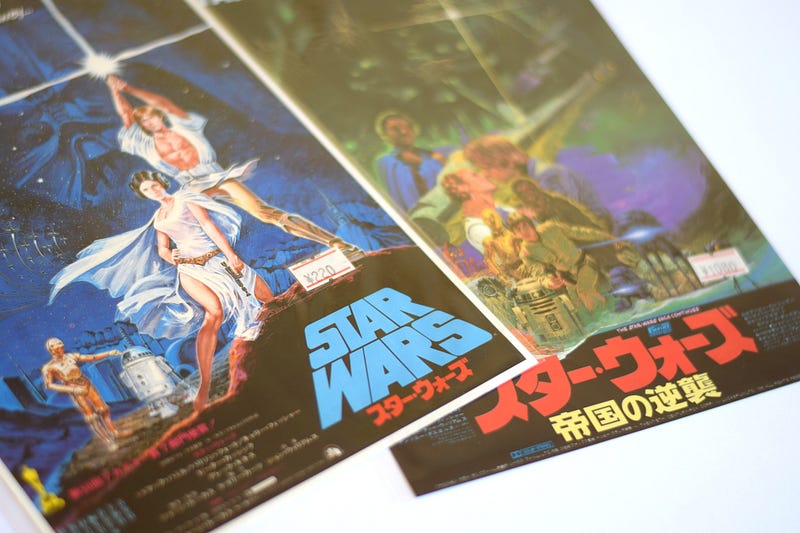

But that wasn’t the end of the story. As with the rise of political neoconservatism, movies saw a classical return to form around a decade later — with the very movies that shaped the generation of kids born around 1970. Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Superman; these cultural classics remain relevant to us today.

But, as with political neoconservatism, the movies of the New Hollywood still pulled in elements of the 1970 pivot: characters drank, swore, weren’t always good. Even the trademark happy ending of Old Hollywood days wasn’t safe. Both E.T. and Titanic, two of the biggest New Hollywood movies of the last four decades, don’t end in happily-ever-afters.

The New New Hollywood: Silicon Valley

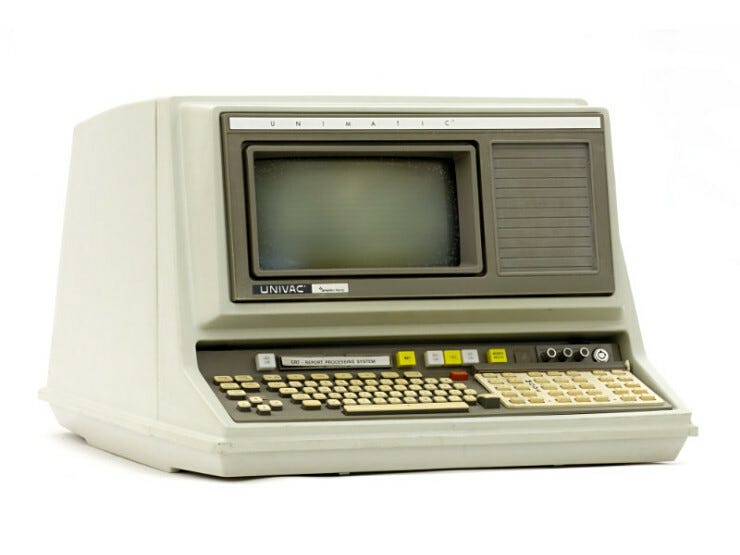

Tech has so permeated our lives and our media that it probably seems almost bizarre to compare it to its SoCal counterpart. And tech had been big for awhile: histories of Silicon Valley cite the more general “electronics” industry as a player in U.S. economic activity even back in the 1960s (though much of it was corporate, military or academic back then). But it didn’t have the It status it does now, and again we find a pivot around our target year: the invention of the microprocessor, in 1971, by a wobbly, but still-major player of today: Intel.

We all think of the microprocessor as enabling something called “miniaturization,” but I’ve always found that word to be paradoxical, since it’s describing how absolutely frikken huge this innovation really was.

It wasn’t just that pre-microprocessor-age computers were bigger; they often required massive amounts of manual labor to assemble, and a significant amount of on-site maintenance when active. Then, in one stroke, the microprocessor took all that away. Picture the slow, painstaking steps we’ve taken toward nuclear fusion happening in weeks instead of decades. Or if we, one day, somebody just rolled out a car that travelled a thousand miles per hour, all while using virtually no energy and totally safe. It basically made one of sci-fi’s holy grails — thinking machines — entering the realm of the everyday in just a couple of generations. Imagine if we cracked warp drive that quickly.

Maybe the computer chip is the biggest paradigm breaker from around 1970 — though, as we’ve seen, it’s not necessarily the path to salvation we may have thought. Actually, that’s a trope: all the things we’ve brought up have led some economic historians to consider the period after 1970 one of decline in American growth. In everything, that is, except computer technology, and its applications. Tech may indeed aid our salvation in the end — or may be the catalyst toward ever-greater doom. Either way, the big boost came right around 1970.

On that note, One More Thing: January 1, 1970 is also Epoch Time Zero for all things UNIX-based. Here’s looking at you, iPhone, Android, and Mac.

The end of optimism?

With all these transitions and upsets, it’s tempting to look at 1970 as the border-line to dystopia. All the above implies a rise in cynicism, a trait most closely associated with the generation bisected at its midpoint by that year. I’m talking about my generation, Gen X. A popular teen movie from 1989 dubbed us the “why bother” generation, in contrast to the (however maligned) idealistic optimism of the Baby Boomers. We may have grown up under Morning in America, but that deceptively positive message was really targeted at Boomers. Lots of us Xers saw it for what Primary Colors called it: bullshit. It’s impossible to watch movies like The Breakfast Club or Heathers and not think how irredeemably hopeless everything feels. Sure, the world has sucked before, but I doubt anyone’s been quite so aware of it, under circumstances so existential, as the generation that grew up in the shadow of both economic decline and the atomic age.

But still, I move that all is not lost. The generations that came after the one cleaved by 1970 hold a different outlook. Millennials were the first to voice full-throated hope again, and took many of the progressive ideals of the 1960s to the next level. Cynics may call it performative or politically correct, but I maintain the conversation moved forward on their watch. And emerging Gen Z, largely the kids of Xers, has again made agitating for social change great again. There, too, 1970 offers an echo: the very first Earth Day was held that year.

Hopefully it makes change-agitators the true inheritors of 1970, the ones best poised to take on the mantle of fixing the world. It’s become clear over the past decade that, in spite of progress in many places, things seem ever more precarious on Planet Earth than they have in a while.

A while, I maintain, of about half a century.

Think you have a birth year with similar significance? I’d be interested to hear about it in the comments below.