A deep dive, with clues from my life’s journey

It’s all over the pundit-o-sphere: we’re in a full-on friendship recession. There’s an epidemic of loneliness. Fewer and fewer people say they have a broad friend circle, and a surprising number say they have no close friends at all.

On the surface, at least in safe(r) Western countries, this almost doesn’t make sense: in spite of all the turmoil worldwide, we live in unprecedented times for connection and communication. If nothing else, you’d think the bounce-back from Covid—manifested in a frenzy of revenge travel—would see people socializing like never before. Heck, even our age’s extant turmoil and uncertainty should help: bringing people together to organize, protest, collectively try to right wrongs—and possibly form lifelong friends in the process. We’re supposed to be living in the age of the global village.

So what gives?

Everyone’s quick to blame social networks and smartphones, and while I think there’s truth in that, it feels like technology’s more a symptom than a cause; plus, these innovations were built to improve communication, not pull us apart.

What I’ve learned from my own journey

Each of us is a world in microcosm—which is why a movie like Inside Out resonates so strongly. This suggests we all may have a little friendship recession living in us.

For me, it came early, anticipating these trends. Closeted gay nerds growing up in the 1980s were practically tailor-made for a loneliness epidemic. Sometimes it even seemed like even the people I counted as friends weren’t so tolerant of my own personal flavor of freak flag. This went double growing up in a small, close-knit, homogeneous community.

In my case, there seemed like no way out. Like the pale blue dot we live on, or the inner world of our minds, my community was all I knew. And for all that it wasn’t too open to outsiders like myself, I figured it could only be even worse in the big bad world outside.

Then, one summer after high school, the paradigm exploded: for one thing, I took a step outside my world, and by golly, it was amazing; for another, my parents experienced a big, traumatic falling-out with their closest friend circle. Boom. Pop goes the world.

In the wake of all that, two things became apparent: one, the little sphere of our youth is rarely, if ever, unshakeable; two, great! There was a whole world out there, offering—maybe, possibly—better options than my origin point.

I’m not sure if it’s because of what happened with my parents, or simply due of the inherent transience of seeking community outside one’s origin point; whatever the reasons, and however more I found my footing and identity in the big world, I never managed to fully shake the friendship recession. Sure, I got great people in my life, but so many more once-great connections have come and gone. And all too many of them took the form of wrenching estrangements—the so-called friendship divorce.

The reasons for these are myriad and complicated, as they often are; I think we’d all be deluding ourselves if we believed that all our estrangements were purely the other person’s fault. Still, regardless of the causes or who’s to blame, we are as much defined by our estrangements as we are by those who stick around.

I think I’m not alone in this, believing that the hill of beans that is our life in this crazy world mirrors something bigger. I mean, think about it: if it’s established that in the past people had more friends and socialized more—then…where did all those friendships go?

To help answer that, let’s go deeper into the past, to a time when it all seemed right. Back to the Good Old Days, when the Baby Boomers were kids.

The Good Old Days: were they really that good?

We’ve heard it many times, How Things Used To Be. When parents belonged to churches, rotary clubs, and bowling leagues; when kids played together until dark, unencumbered by technology, with only their bikes, their park swings, and their imaginations to live out an idyllic childhood.

I don’t think that’s totally off-base. But I also don’t think it’s the whole picture.

Like World War II vets who seldom acknowledged that war’s horrors—it took Saving Private Ryan, a half-century on, to explode that John Wayne myth—I suspect Boomers, the generation before mine, often don’t acknowledge how tough it was for them beneath the surface of their idealized past.

Never mind the obvious parts, like how awful it was for most anyone LGBTQ+, or for people of color; even in the catbird seat of the white middle-class, people had to live with the distant but plausible shadow of nuclear apocalypse. Closer to home, the established social harmony concealed what was beneath the surface. Example: take the movie Stand by Me, possibly the quintessential Boomer nostalgia feast. Its closing line, typed by its author, the adult recounting the story decades later:

I never had any friends later on like the ones I had when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?

Maybe the statement was intended to be more ironic than anyone realized. I recently did a full rewatch of this 1986 classic, and…holy crap. Has anybody misty for the Good Old Days actually seen this movie? Those kids, the film’s main characters, these loyal-till-death-do-us-part buddies, are basically total jerks to each other. Their friendship consists of trash-talking and insults. They behave like worst enemies, only briefly punctuated by moments of heart-rending vulnerability. Once this may have been called just boys being boys; but I think I see why the term toxic masculinity came about.

Not that they don’t come by their horrible behavior unfairly: they’re all from messed-up backgrounds riddled with sadness, anger, and abuse; they’re repeatedly bullied by a gang of older kids; heck, the entire adventure that’s the movie’s McGuffin consists of an overnight camping trip…to go see a dead body. If you ask me, this tale — based on a Stephen King novella — is way more frightening than anything the author cooked up in his ghost stories (full disclosure: huge fan).

Why things are worse now (but shouldn’t be)

OK, then. Coming back to now, when we live in so much more enlightened, aware, attuned—dare I call them “woke” times—then…why don’t we have the opposite of a friendship recession? Are all of us just whiny, ungrateful brats, willfully isolating ourselves, too obtuse to see just how gosh-darned good we have it?

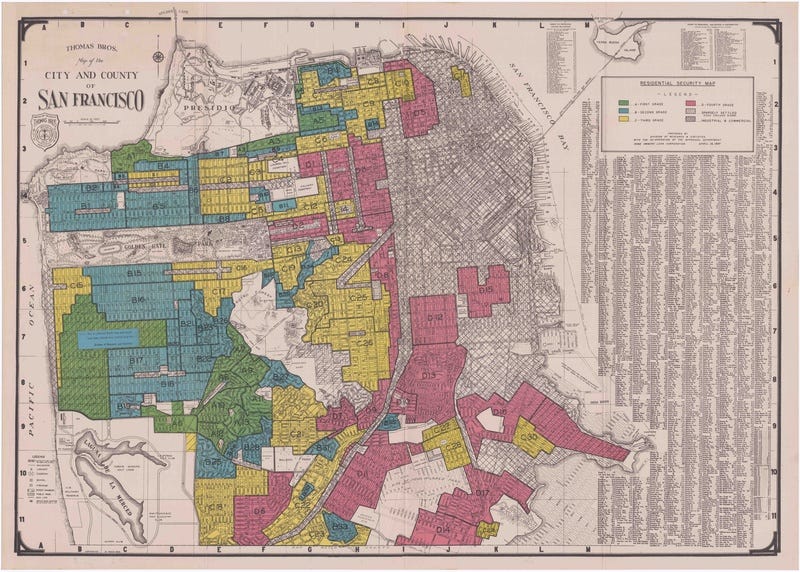

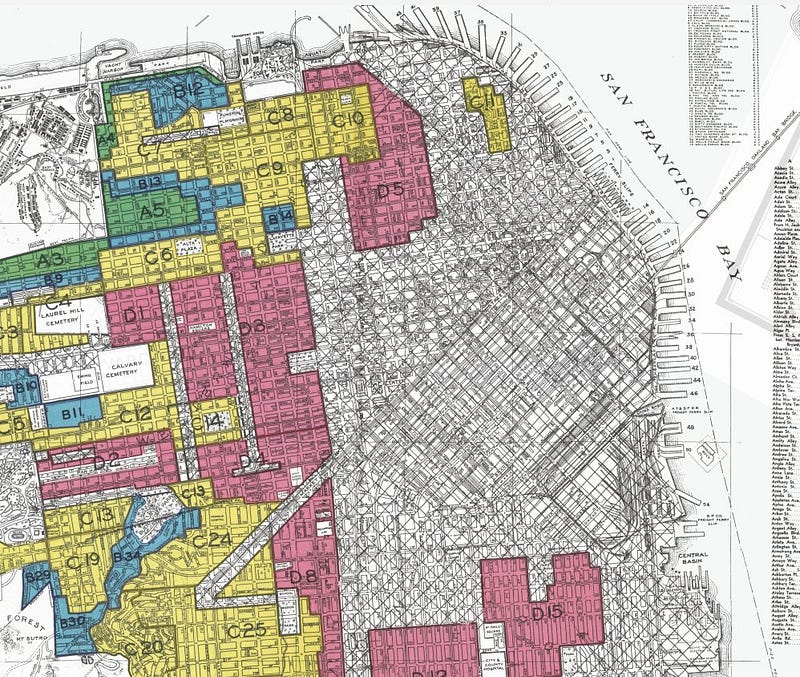

It’s important to remember that aggregate statistics of how good everything is—GDP per capita, median wealth, average life expectancy, and the rest—obscure a reality author William Gibson predicted and has become a trope if not a cliché: The future is here, it’s just not equally distributed.

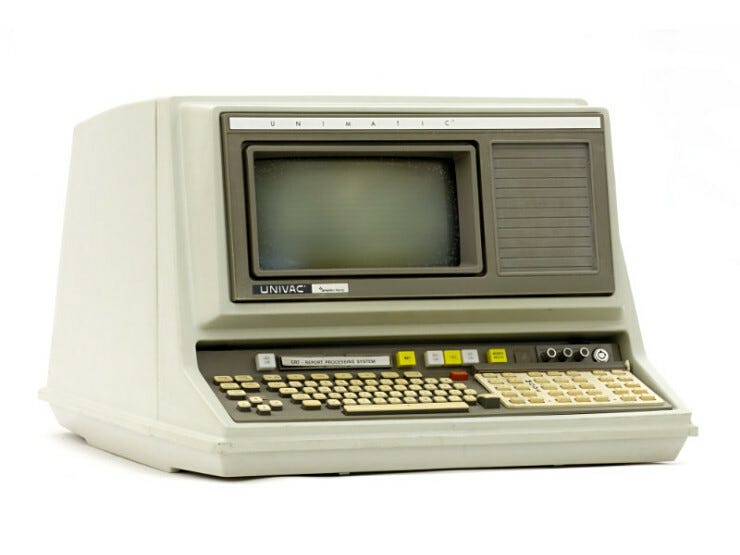

Much ink has been spilled on how the past fifty years have been decidedly different than the century that preceded it. Some have called it the post-industrial age, where computing and communication technology overshadowed industrial-era innovations (think about how similar today’s passenger jets are from those of the 1970s, compared with computing devices from then and now). But there are two sharply opposing trends that also define the age, the past half-century, the era in which the friendship recession and loneliness epidemic took root.

Trend One: Free to be…you and me

I actually think the forces on the political right have a point about what they now call wokeness: we do live in times of greater emotional fragility. All that stuff repressed by the GIs in World War II, and even many of the Boomers, their kids—empathy, sensitivity, emotional awareness—are front and center now. Maybe it started with the Flower Children of the 1960s. Maybe it took off after Oprah made child abuse her cause célèbre, starting in the 1980s. Whatever the sequence of events, Gen X (a.k.a. my crowd) arrived into a world that idealized connection, kindness, and—yes—companionship. Consider the 1970s kids’ album (and companion TV special) Free to Be…You and Me; I still get choked up listening to songs like “Glad to Have a Friend Like You,” about an oddball boy and girl who become best mates, bonding over baking cakes and fishing.

There’s more: consider Sesame Street, Mister Rogers, or any number of 1980s sitcoms. Again and again, there’s the unshakable bond among friends. Go further, and you’ll find amity on Star Trek’s Enterprise, with the Skywalker gang from Star Wars, or, heck, on practically any buddy cop show.

Thing is, all this apparent warmth and connection—as represented in media and on the surface perceptions of other people’s lives—crashes against the other big force of the past half-century.

I’m talking, of course, about the rise of full-contact capitalism.

Trend Two: Greed is good, and those other ideas lying around

Even as popular culture lionized friendship, another trend was rising. Call it the flip side of eliminating the more coercive, hypocritical old-school social organizations of yore—let’s be honest, how many of those Rotary Club regulars actually liked each other? The 1970s saw the rise of the Me Generation. Surprisingly, this trend really found purchase on the economic side of things.

And that’s where, I think, things really came undone.

There’s nothing inevitable about sixties idealism’s push toward individual expression somehow ending us up in a Gilded Age-style plutocracy. But that’s how it panned out: a legitimate rejection of the stultifying 1950s, with its merciless cutting down of any tall poppies (or, more accurately, the odd-shaped poppies) among us.

But we never fully replaced the institutions of 1950s; instead, we embraced a hardcore flavor of individualism to take care of everything. Then, the rival economic system, one where everyone called each other comrade, crumbled almost overnight. It took economist Milton Friedman, and his ideas lying around, to come to the fore. We transitioned from Free to Be…You and Me to Greed Works.

And I think we broke friendship in the process.

Don’t believe me? Hear the ever-quotable Gordon Gekko once more:

If you need a friend, get a dog.

What this meant, in our everyday social workaday spheres, was that, while, sure, we were ever more free to be who and do what we wanted, we were also now in throat-throttling competition with everybody else for a diminishing share of the economic pie. We replaced the Boomer childhood of a broad-based middle class with the classes on the Titanic: a huge majority with little or no economic security (90% of the population); a smallish minority of upper-middle-class (the top 90–99% of the economic distribution); all of whom fight constantly to belong to the top 1% (those whose income is derived from wealth).

BFF platitudes die hard in a zero-sum world. Friendships become increasingly transactional. It puts even the strongest of bonds under strain. When so much of life feels like a desperate race, a high-stakes competition for status, standing, and material security, personal connection is the first and biggest thing to suffer.

The four horsemen of the friendship apocalypse

Of course, none of this is totally unprecedented: people have fallen in and out of friendships (and love, and familial bonds) for as long as there have been people. But this flavor of it has its own causes and behaviors. To add to all the ink that’s been poured into this subject, let me add my own perspective. I can identify four personality traits that serve to shatter friendships. I believe we all retain bits of these traits; however, in an era where everyone’s scrambling for the same few lifeboats, any of these traits is liable to metastasize and take us over.

Highlight-reeling

We all know this one, a potent force in our fake it till you make it culture. We’ve all heard tales of other people’s fantastic lives, fabulous careers, endless circles of friends, flawless marriages. An effortless, perfectly curated life made manifest by the power of the prosperity gospel.

What’s wrong with that? Doesn’t a life well lived deserve to be flaunted? Is it not virtuous to be happy for the good, fulfilling lives of others? Sure…but that’s not what highlight-reeling’s about. It’s never about a comprehensive picture of what’s really going on in someone’s head or life. Plus, it’s not about you sharing in their bounty. As I’ve experienced it, highlight-reeling seems intended to make others feel worse. Maybe to weaken them, a little, stifle them as prospective competition.

Counter-point: isn’t resenting highlight-reeling just jealousy in disguise? Actually, yes. But that’s sort-of the point. Highlight-reeling’s patently fictional depictions of existence are such that it’s hard not to be jealous—even if we know, somewhere in the recesses of our brains, that it’s mostly a fake-out.

As with all of these behaviors, I recognize there’s more going on with highlight-reelers under the surface. Oftentimes, it conceals real inner pain that our competitive society discourages us from expressing. Whatever’s going on inside, highlight-reeling has now reached the commanding heights: our re-minted President practically embodies this trait.

But you don’t have to limit it to the top: find me any large-ish group of friends and it’s fairly likely there’s some measure of highlight-reeling going on.

The hard-luck case

For a long time I was drawn to folks in this state. In fact, for a long time I thought I was this state. It’s seductive: hard-luck cases form powerful bonds, and for good reason. Podcaster professor Scott Galloway, in an aptly-titled blog post, points out that “the cocktail that’s made us the apex of apex predators is cooperation on the rocks of conflict.”

So how can it go wrong? Simple: circumstances (and people) change.

Again, this is nothing new or unique to our times, but in our present-day über-capitalist world—where job security, affordable housing, college, health care, and retirement have become lottery-ticket uncertain—it’s especially fraught. Even among those who start at similar places, or in the same friend circle. With the unpredictable socio-economic sorting that goes on these days, not everyone ends up in the same place. Some might make it, find their footing, establish themselves even if they began life as hard-luck cases…and some do not.

The great ideological fault line

We’ve heard endless talk about why we’re polarized politically; I maintain it’s the same reason we’re polarized socially. It’s not because of disagreements in the margins about taxation rates, or the effective role of government in a society. It’s because the two political philosophies of our age—roughly characterized for the past two centuries as Right and Left—have divided the world into camps built out of different ways of looking at the world.

It’s been said the the Left borrows from Rousseau, with his ideas that people are naturally good; it’s only modern civilization that’s messed us up, divided us against each other. Put us back in nature, out of our so-called civilization, and we’d get along a lot better.

The Right, by contrast, is said to stem from Hobbes, who believed that, without a strong, hierarchical order, we’d regress to savagery. Hobbes’ catchphrase for his take on the state of nature has become legendary: nasty, brutish, and short. It’s also often termed human nature, which is supposedly something utterly immutable and irretrievably selfish.

Friends have been having political debates since time immemorial; but in today’s climate, it’s particularly charged. Each side views the other as an existential threat, and how could it not? When so few have economic security, whatever side they’re on feels like it’s fighting the last battle to save the world. This acts like a jet turbine for our belief systems. While it’s less common for friendships to end due to political shifts, the mere fact that we’re sorted into these tribes in the first place eliminates large swaths of the population from ever commingling in the first place.

Friends with money, entitlement, and other asymmetries

While highlight-reeling is an attempt to sow inequality where it doesn’t exist, and hard-luck cases are embattled allies taking on the Empire together, there’s another dimension that inequality has foisted upon our friendships: what happens when there’s substantive inequality among friends from the start?

It’s less common, since friendship economic sorting is as prevalent these days as the political. But when there is imbalance between parties, sometimes we attempt to correct it with a dollop of noblesse oblige. Example: from early on, I’d been taught to lionize the 3am friend: the person who, as with Hillary’s campaign commercial from 2008, is always there, available for whatever trouble is afoot.

Noble indeed, but it’s also problematic. In societies with strong social obligations, codes of conduct attempt to keep things balanced. But we’re all on our own now, and those checks are gone. Sometimes it gets so far out of whack that you forget who’s privileged and who isn’t—witness the Karen phenomenon from a few year back. To say nothing of nearly any media depiction of rich kids.

Meanwhile, about that technology thing…

And so, back to tech. There’s good reason to blame it: the friendship recession really accelerated in the 2010s, right when smartphones came out. Sure, things may have started to worsen right when full-contact capitalism got going, but tech proved the lethal ingredient.

But did it have to be? Remember, the smartphone/social universe/filter bubble phenomena are outgrowths of Milton Friedman-era capitalism, where all companies care about is shareholder value, and build their algorithms accordingly. So let’s imagine a different path.

It’s easy to forget that it was not so long ago that tech platforms were widely considered forces for good. When Googling became a thing, it felt like something of a miracle: the entirety of human knowledge at your fingertips. When social media was young, people used it to organize Arab Spring protests. There’d emerged something of a consensus that computing technology, as molded by Silicon Valley, was beneficent.

So what if things had kept on going that way, and we’d kept the good parts of capitalism—risk-taking, entrepreneurialism, respect for honestly-attained social capital, open (but supervised) markets—but ditched the toxicity—the gladiator mindset, the doctrine of hyper-concentrated ownership, the alienation of workers with no stake in the future? Imagine what tech would look like then.

Actually, not just tech. Practically all innovations—petroleum, nuclear power, electricity, commercial air travel—began with hopeful origin stories about their anticipated use.

Does this mean that all good technology ultimately goes bad?

Actually, I don’t think so. But I do believe that our acceptance of today’s zero-sum inequality has allowed our inventions to become corrupted. Those inventions can then be used to turn us on one another. But in a different societal construct, with different societal attitudes that serve to uplift the good while keeping constrained the less savory aspects of—yes, I’ll say it—human nature; well… many things become imaginable.

I really believe it’s as simple (and as impossible-seeming) as a wholesale mindset shift among every one of us. For all of us to unleash our capacity to Think Different (not the first time I’ve used this, I know) about the nature of our hierarchies, and the composition of our relationships.

I’m not proposing some sort of political revolution, by the way—we all know how those turned out—only that I hold out hope that something, somewhere, fundamentally, will click into place in the mess of a social contract we’ve made with each other. And hopefully it won’t take a cataclysm to turn us all wiser (though if Star Trek is any metric, it might).

I know we’re far from there still, marooned as we are on our lonely islands. But the seas are rising fast. How long can we go on like this before the yearning for the connections we once had becomes too loud to ignore?