What an unlikely group of thinkers tells us about our interesting times

Amid all the self-analysis and hand-wringing going on with progressives in the wake of the 2024 U.S. election, there’s one group whose reactions will be especially interesting to watch.

The existence of this group eluded me for a long time. That is, until watching the TV series Young Royals. Groundbreaking as it was for its frank depiction of a very unconventional queer romance between a young Swedish prince and a working-class Latin American immigrant who meet at an elite boarding school, something stood out to me: the other snobby students label Simon (the immigrant kid, played beautifully by Venezuelan-Swede Omar Rudberg) a “socialist.”

I didn’t get it.

I mean, they’re in Sweden, for heaven’s sake, the nation held up as standard-bearer for a modern-day socialist economy. Why would kids in such a country consider that an insult?

Then there was the time, back in 2016, during the Hillary-Bernie Democratic primaries. A boss of mine from India said she’d never—never—support Bernie Sanders because he, too, was a socialist and (as she put it) “socialism is terrible!” She didn’t elaborate, but I know India had a flirtation with this form of governance in decades past.

Cut to today, and there’s this guy, a Norwegian CEO lauding America’s work-life-imbalanced workforce, whom he terms “ambitious.” That made me reflect on my own attitudes towards America in my youth…and then it all made sense.

The Left, the Right…and the other Right?

The left-right divide in the United States—despite reshuffles and realignments—is pretty well understood: on one side, it’s God, guns, and greed is good; on the other, it’s warriors for social and economic justice who, somehow, never seem to live up to expectations. See: this year’s election results.

But there are others who don’t fit neatly in either category. They make more sense now that I see the pattern—and realize I used to be one of them.

I call them the Overseas Conservatives.

Who (and what) is an Overseas Conservative?

Obviously, the United States didn’t invent conservatism—I’m not suggesting that. The concept, in the form and ideology we know today, began in Revolutionary France, where the seats of the National Assembly were organized: establishmentarian types on the right, reform/revolution types on the left.

That said, the American flavor of conservatism seems unique. Maybe some of that’s historical: America never had a monarchy, and very vigorously threw off rulership by one early on. Capitalism and meritocracy were new concepts in 1776, but for America, it was money and markets from the word go. Meanwhile, as religion slowly receded all over Europe in modern times, America’s conservatives held on to it—so much so that the term religious right is as American as Big Macs and apple pie.

Disclaimer: I know concepts of left and right are (and probably always were) oversimplified, terms that bundle together many strands of thought and policy notions. Nevertheless, the labels have stuck, so please indulge this exercise with that in mind.

Also, I’m not focusing on everyone considered a right-winger outside the U.S.A. That’s way too broad a catchment group. What makes Overseas Conservatives stand out is their non-American-ness, twinned with their association with America. Either they live here now, immigrated here by choice (as I did), or perhaps were refugees of some sort. Or else they’re pundits who remain outside these shores, but for whom America is their beat. But they all cut their teeth elsewhere, their life experience formed outside this country.

Exhibit A: Christopher Hitchens

The OG of them all, the late Christopher Hitchens actually began life (as so many neocons did) a leftist, but drifted rightward over the later two decades of his life. In some ways, he almost doesn’t make this list, since he held a great many positions that still today are defined as progressive: a hardcore atheist, he opposed the War on Drugs, and supported same-sex marriage. But after 9/11, after years of criticizing U.S. foreign policy of yore, he shifted, supporting Dubya and his wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. He came to see Islamism as Public Enemy Number One. This is something we’re going to see a lot of with Overseas Conservatives, and why they’ve come to stand with America so profoundly.

Exhibit B: Andrew Sullivan

Another early figure, Andrew Sullivan is equally a study in contrasts. Gay and out for decades, his early career reveals a mixed trajectory: writing for the (conservative) British Daily Telegraph early in his career, then stints at The New Republic, The New York Times, and The Atlantic. He’s a terrific writer (as many in this group are); his piece on America after 9/11 is one I’ve cited many times, and still find to be one of the most emotionally moving depictions of what it was like in this country in the days following that terrible one. He was an early and ardent supporter of same-sex marriage and Barack Obama. And then…there’s his Substack, with its skepticism over trans issues, and its fixation on the wokes (something that’s also something of a trope here).

Exhibit C: Niall Ferguson

A Brit who’s a bit less focused on America than Hitchens or Sullivan, he nonetheless covers it a lot on his beat, and even became a U.S. citizen in 2018. He’s known more for his triumphalist notion that the British Empire was better than the rest of the European imperialists; he early on saw the potency of Trumpism, and has been supportive of the now-again President-elect on occasion. He’s also big on the anti-Islamism train, going so far as to buy into the Eurabia conspiracy theory. He goes even equated Islam to the threat of Bolshevism, believing the Islamists literally want to take over the world as the early Communists did.

Exhibit D: David Frum

A Canadian like myself (I remember fondly his late mother’s newscasting career in our native homeland), Frum rose to prominence in America as a speechwriter for George W. Bush. Even those unfamiliar with this crop of conservatives almost certainly recognize words he wrote. Three of those words became the iconic line of the century, when Dubya termed Saddam’s Iraq, Islamic Iran, and totalitarian North Korea the axis of evil.

This is more than mere wordplay; it’s what unites Overseas Conservatives and onshore right-wingers alike. They’re often spoiling for a fight against some existentially-threatening bad guys looking to take down the West. Not that they’re totally wrong, I maintain, but their fixation on making these admittedly lousy actors on the global stage into Disney villains strikes me as hyperbolic. This has long been a hallmark of many flavors of conservatism: Othering others, leaning hard into patriotism and even jingoism, always wanting an ever-bigger military.

That said, Frum has grown ever more critical of America’s conservative standard bearer, the Republican party, and has even greater distaste for the prior/future President.

Exhibit E: Jordan Peterson

Another Canadian, Peterson’s a weirdly mixed bag: supportive of universal healthcare, drug decriminalization, and wealth redistribution. And then…there’s his deadnaming actor Elliot Page. His savaging of political correctness. His denial of climate change. The list goes on.

Sometimes I wonder if that’s all it is with so many of these guys — and notice they’re all guys, white ones to boot: the taking of extreme, dissonant positions purely for shock value. I myself remember being this way in my youth, the thrill of being the enfant terrible of your cohort, shocking and horrifying all these progressives (or as it’s now known in America, owning the libs). But is that a deep enough bench to build an ideology? Peterson often has other, smarter things to say, but not every political Bad Boy does. Now that we have a President-elect with his own Bad Boy rhetoric, we’ll see if folks like Peterson go high or low.

Exhibit F: Douglas Murray

Another queer Brit, but this one more off the chain than Andrew Sullivan. Here again, we encounter the usual suspects: more Eurabia fixations, more fulminations on woke culture and its existential threat to all that is good, fair, and decent.

Murray reminds me of Log Cabin Republicans I worked with in years past. Why, I wondered, would anyone want to belong to a group so hostile to this fundamental part of yourself? One notion sees the LCR as queer Uncle Toms, or as Jewish folks call such sellouts, kapos. These were, for the uninitiated, those Jews who attempted cooperation with the Nazis in a deluded attempt to somehow countervail the effects of the Holocaust. You can guess how well that turned out.

I don’t think Murray’s quite that far gone, though some of his stances strike as unhelpful to the LGBTQ+ community. Actually, he doesn’t even think much of that community, or as he put it, queerness “is an unstable component on which to base an individual identity, and a hideously unstable way to try and base any form of group identity.”

Seriously, dude?

There’s more. He was one of the first to label Kamala Harris a diversity hire. And this is where the limits of Overseas Conservatives become apparent. I maintain they possess a blinkered view of America. This charge against Kamala’s a perfect example. Many of Murray’s defenders claimed he’s simply parroting what Joe Biden said in 2020: that he was explicitly seeking a female minority to round out the ticket. Surely that’s a diversity hire, no?

Not hearing the dog whistle

Political strategists as far back as Lee Atwater understood that, in post 1960s America (some may call that decade the dawn of wokeness), it’s unacceptable to express overt racism. Race science is discredited and vilified. It’s political suicide — to say nothing of scientifically false—to claim superiority of one ethnicity over another. But Atwater must have sensed that many in 1980s America still held such biases deep down. So instead, his cohort found ways to sneak in such notions.

Diversity hire is one of those notions. Maybe Murray was aware of it, or maybe he wasn’t, but in America of today, this term doesn’t describe a benign move to uplift certain demographics—such as, say, preferring a queer actor for a queer role in a TV series. No. It’s much more insidious than that. It’s to suggest that a person of color is somehow incapable of fulfilling that role. Tragically, I fear that, in some quarters, these odious interpretations will be used to explain the outcome of the U.S. Presidential election of 2024.

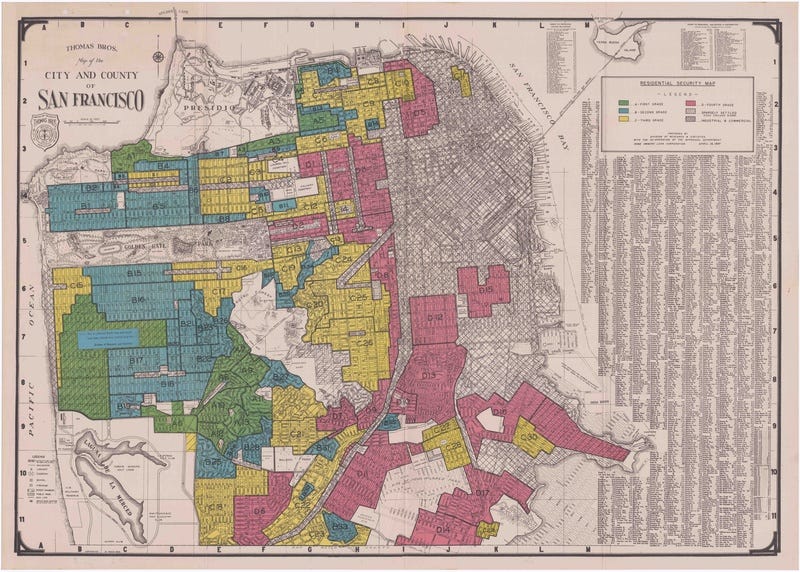

I’ve discovered that Americans who grew up here and know their history intimately understand these nuances: Beyond slavery and Jim Crow, there have been decades and centuries of educational disenfranchisement, disinvestment in communities, histories of neighborhood redlining, voter suppression, and a host of other ignominious actions undertaken against minority communities. Their struggle is real—so much so that, if anything, a woman of color has to be even more qualified than an equivalent White male to land the same position.

I wonder if Overseas Conservatives like Murray see all that. I sure didn’t when I thought that way.

Can we learn anything from the Overseas Right?

Surprisingly, I think we can—if only to solidify the notion that ideologies are complex, fluid things. Many progressive sacred cows—abortion, same-sex marriage, drug decriminalization, atheism or agnosticism—are baked into the beliefs of many of these non-Americans. They’re almost old-school Republicans, those Chamber of Commerce types who want nothing more than for free markets to be given a chance, and for government to be lean, efficient, and minimally involved with our lives.

Well, with one huge exception: that need to fight the boogeyman, whatever current flavor that may take, military spending no object. Perhaps it’s no surprise that the biggest geopolitical preoccupation of Overseas Conservatives these days is radical Islam. It’s more of a thing in Middle East-adjacent Western countries, or those with historically looser immigration policies than the United States. And there’s some truth there: there indeed exist Islamic nations with aims to do harm to the West in general, and America in particular. Their sponsorship of all manner of unsavory groups is well established.

While some progressive pundits pull from the anti-war history going back to Vietnam, the old saw that the Dems are weak on defense seems demonstrably false. Ronald Reagan helped engineer that perception—think Jimmy Carter and the Iran hostage crisis. Yet America’s government and military has continued to practice realpolitik—party in power notwithstanding—often to the chagrin of its progressive citizenry and (some) in academia. And yes, in those circles we do see it: post-colonial discourse blaming European imperialism for all troubles in the world. The notion, among some, that the West is in fact responsible for the rise of radical Islam.

Here I’d say Overseas Conservatives may have a point: the political left’s acquiescence to Islamist groups is the biggest geopolitical miss, I’d venture, since New York Times journalist Walter Duranty reported on Stalin-era Soviet Union. Take this social media post during last spring’s Columbia University protests:

So, OK, we get it: idiotic geopolitical thought, and hyperactive policing of jokes and pronouns, grates on many. Ideologies, no matter how noble, can go awry. But I think what Overseas Conservatives, indeed all conservatives, seem to miss is that trolling the other side with provocative extreme-talk doesn’t fix underlying problems. Oftentimes, problems are complex and nuanced, and involve looking deeper and Thinking Different—and when Overseas Conservatives apply their outsider insight to such things is when I think they shine.

That said, I understand the Overseas Conservative appeal to those on the front lines — whether in the U.S. military in the Persian Gulf, or among the beleaguered citizenry of Israel/Palestine. So let’s take the Eurabia charge at face value: even with the migrations of recent decades, it’s unlikely Europe’s Muslim minority will even reach 20 percent in future decades — about the same as the Latino community in America (interestingly, it doesn’t seem most Overseas Conservatives are as interested in migration from America’s southern border as some domestic conservatives have been of late). And some have theorized that many of the issues Europe has with immigrants from Muslim immigrants have more to do with failure of assimilation, or lack of economic and social opportunities.

To answer that charge, there’s a well-worn (if imperfect) antidote to be found right here in the Overseas Conservative’s backyard: America, with its long tradition of bringing in outsiders and making them part of the greater polity. As a son and grandson of immigrants, and an immigrant of sorts myself, I’d even extend that to the recent influx of migrants from America’s south; so many of them are fleeing economic and political tyranny, and deserve our help. Why not hold our governments to doing it properly, in economically beneficial ways, instead of indulging in more xenophobia? Sure, some immigrant groups are slow to integrate, or self-segregate to varying degrees, but in the end, Barack Obama’s rhetoric about the bonds that unite us is real.

Learning from each other (and from history)

In a way, conservatives have it easier than progressives: it’s much easier to embrace the status quo, or harken back to some mythical past that never really existed, than it is to push for change, risk getting it wrong — and disappoint vast constituencies in the process.

This leads me to my ultimate concern about Overseas Conservatives, the real reason I abandoned their philosophy earlier in life. As constituted nowadays, it seems to me their conservatism embraces two toxic beliefs: essentialism and the just-world hypothesis. With essentialism, there’s the view that, things are their essence, and cannot be changed. Written in the stars, encoded in our DNA. There will always be poverty and bad people, so stop trying to fix them. The just world hypothesis, meanwhile, holds that the universe makes sure everyone gets what’s coming to them. Billionaires and mega-corporations legitimately earned what they have, so stop trying to raise taxes, or force social responsibility on them.

It seems to me these philosophies have utterly warped our economies, leading to a harsh, zero-sum form of competitive capitalism that leaves tens of millions looking over their shoulder, worrying about their economic and job security as companies disproportionately reward large shareholders and top executives. What good is America’s high-performing GDP if it only benefits a relative few?

I’d like to see Overseas Conservatives say more about those issues, speak ever more truth to real power, instead of fixating on the other side’s occasional craziness. In times past it was easy to tar the left as equally bad. But now? There really is no “far left” in America. Think about it: Communism has been well and surely defeated. Most formerly leftish ideas like climate change, same-sex marriage, or drug decriminalization, are broadly popular across the political spectrum. No serious U.S. politician is talking about forced collectivization, a secret police to punish counter-revolutionaries (or those who misuse pronouns), or prohibiting migration. Most of them are for the sort of mixed economies we see in European countries. As Bill Maher once said of Hillary Clinton, “Che Guevera in a pantsuit she is not.”

If I had to pick a favorite, I think David Frum offers a possible path forward—points for expat Canadians named David. He’s renounced and repudiated so much of what he once believed, embodied in a marvelously nuanced piece in this month’s The Atlantic. I’d like to think more of these folks—all of whom I concede are superb thinkers, by the way—will look at this election and, rather than engage in the usual smug, self-congratulatory right-wing triumphalism, aim to Think Different.

Because we need them, indeed everyone, to begin thinking that way, as the incoming political class of America circa 2025 promises a very interesting spectacle.